The Mirrors of Recognition

In Plato’s “Symposium,” Aristophanes says Zeus split humanity in two, leaving each to search for its other. What we seek isn’t another person, but their reflection makes us whole.

by Monica Lynn Moore

On Recognition: The Human Longing to Be Seen

“We can only be more loving when we recognize ourselves in one another. Perhaps by turning to the past, we can recover a richer understanding of recognition.”

At the age of 45, I embarked on a journey to study Ancient Greek and philosophy, including spending several months on the tiny Greek island of Samos with a handful of students half my age…yet seemingly twice as smart. What could be characterized as a midlife crisis was driven by a romantic notion of the humanities and a longing I couldn’t quite place but had something to do with a growing sense of disconnection.

The narratives of today feel so alienating—and there seem to be so many, they cancel each other out. Between political divisiveness and technological depersonalization, it often feels like we’ve past the point of no return. I was searching for something more, something verging on the eternal… A north star. But I wasn’t sure how learning Greek would help. And wasn’t I too old to be a student? Again?

All my friends, including my boyfriend, thought I was crazy. But the gypsy in my soul pushed me forward on the plane to Athens, with a copy of the Iliad in one hand and a handbook of Greek grammar in the other, as I said my tearful good-byes. I wanted to go. But it also felt a little reckless, leaving my life in midair. A decade ago, I would have been unfazed. Now, I was leaving my future, and the people in it, behind.

T.S. Eliot wrote, “Someone said, ‘The dead writers are remote from us because we know so much more than they did.’ Precisely, and they are that which we know.”

To study the great works of earlier ages is to cross a threshold into another world — one whose language is foreign not only in alphabet and grammar, but also in era and belief system. In learning Ancient Greek, I found myself entering the minds of Plato and Aristotle, and, through them, glimpsing something of my own reflection. Immersive study of an ancient language does more than teach words; it restores a living connection to the past. The theme of recognition became my guiding star throughout the year.

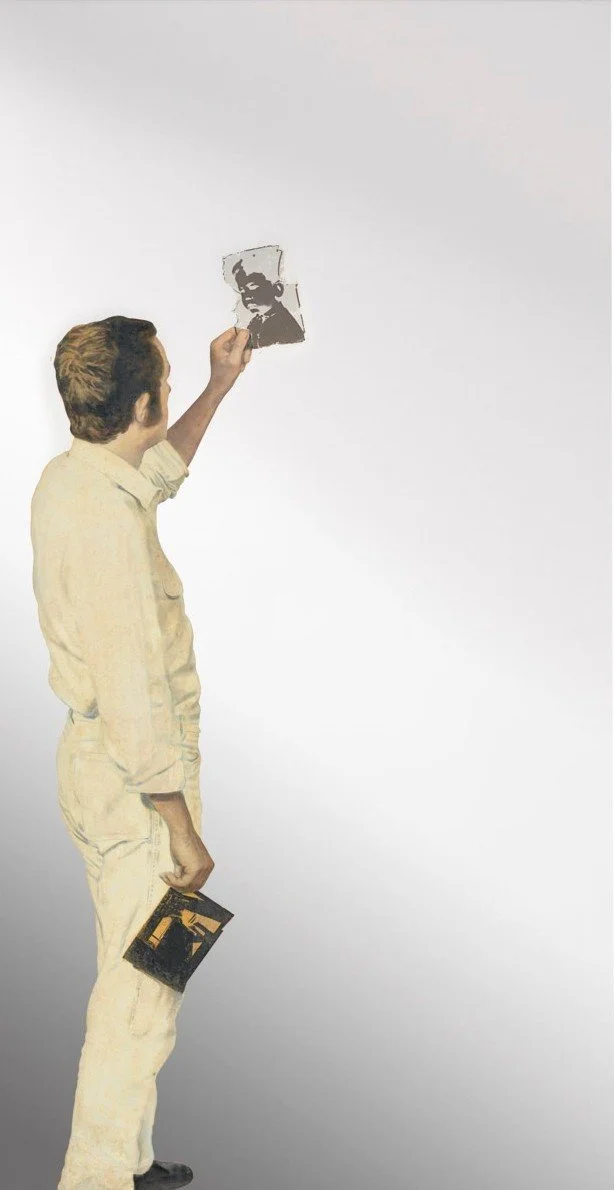

“Man looking at a negative” (1967) is an exceptional early Mirror Painting by Michelangelo Pistoletto.

The need for recognition is so fundamental that it’s wired in us from birth. A baby, moments out of the womb will look around immediately for a face to recognize it and know its needs will be met. “Still face” experiments in which mothers are told not to respond to their babies show that when the mother is expressionless and does not acknowledge her child, the baby squirms, cries, and then falls apart.

As adults, we carry this forward, aching to know and be known. To really see into one another, the essence of intimacy, or into-me-see, as psychotherapist Esther Perel puts it, is the deepest form of recognition. We use the gaze of others to continually refine our sense of self, for better and for worse. It’s up to us to choose where to direct our attention and which reflections to trust.

It is deeply human to feel somehow incomplete without the gaze that affirms us — we need witnesses to make ourselves, and our stories, whole. Why else do we instinctively call a friend the moment something important happens?

Plato’s Symposium (c. 385–370 BC): Athenians at a banquet share spontaneous speeches on love, life, and desire.

In Plato’s “ Symposium,” Aristophanes describes how humanity was once whole until Zeus split us in two, leaving each to wander in search of the other: “And every one of us is forever looking for the token that fits with ours.” What we seek, perhaps, is not only the other person, but the perspective that completes our own.

Two important things come from recognition: our sense of identity and our ability to relate to one another. The ancients understood this cosmically and saw recognition as part of a rational order (or lógos) woven into reality itself. They believed we are not isolated individuals, separate from the universal, but rather active participants in an ever-unfolding consciousness. A sense of belonging is not something we need to search for, only to remember. Could this view of recognition still be a thread that holds us together today?

“People don’t see the world with their eyes, they see it with their entire life,” writes David Brooks in his book, “ How to Know a Person.” He goes on to add, we may not only hold different opinions about the same world, but we literally see different worlds. At times, it feels like a fight to the death over whose version will win. Kindness, generosity of spirit and dignity can quickly fall away in our rush to be right.

Artist Rachel Harrison - colored pencil over pigment inkjet print.

While it may be not be possible to bridge the ever-widening gap, we should at least feel galvanized to try. W.H. Auden wrote a line of poetry I always return to, “If equal affection cannot be, let the more loving one be me.” We can only be more loving when we recognize ourselves in one another. Perhaps by turning to the past, we can recover a richer understanding of recognition — and, in doing so, restore something of our shared humanity.

“Concepts create idols; only wonder comprehends anything. People kill one another over idols. Wonder makes us fall to our knees.” –St. Gregory of Nyssa

Monica Lynn Moore – professor, writer, and voice behind “The Beauty of the Way.”